First launched in 2014 in response to the HIV/AIDS crisis, International Zero Discrimination Day (March 1st) was created to help exercise the right for everyone to live with dignity; to promote inclusion, compassion and peace; to educate people about discrimination and how to challenge it; and to ultimately start a global movement to end discrimination altogether.

This year’s theme is “We Stand Together”. Read on to learn why that sentiment must resonate with millions to counteract the current wave of hate that so many are being forced to endure.

Hate: A Learned Behaviour

The very reason observance days like this exist is because people make the choice to hate. Though hate has existed throughout all of modern society, none of us were born with hate in our hearts. Babies don’t enter the world deciphering between race, religion, gender identity or sexual orientation. Any biases they may form against anyone who differs from them are purely taught, or learned, as they get older.

A piece published just last week in Psychology Today, examines the reasons why some learn to hate:

Fear

The main driving force behind any kind of prejudice is fear. When something (whether that be a culture or belief system or even skin colour) is different from one’s own, unless they have direct (positive) experience with it, there is a danger that fear will develop from the discomfort of misunderstanding whatever that “something” happens to be, then manifest into something worse.

Stress/Anger

When people of any age are overwhelmed by their circumstances, a natural instinct is to assign blame elsewhere for their troubles. Emotions are directed outward and the target is by default someone or some group that they find to be opposite of them.

‘Us vs Them’ Mentality

Our inherent human trait of forming tribes based on our cultures and beliefs can work against us when pride for one’s own group transforms into unjustified levels of superiority. This can lead to the rationalization of violence.

Personal Experiences

If one has an issue caused by a person in an opposite social group or is brought up in a home that teaches them “those people” are bad, they can absorb and project that hate. The same goes for people who may identify with such a group, but because of their upbringing or environmental influences, feel ashamed by it and reject the association as a result.

It’s not all bad news, though—because hate is a learned behaviour, it’s also a trait that can be unlearned. Through exposure to other cultures, awareness events and education, we can turn the tides:

- The Southern Poverty Law Center has prepared a community guide on how to respond to hate.

- Direction on how to combat hate speech, is provided by the United Nations.

- Project Implicit invites those 18 or older to take a free test in a variety of categories, to reveal any inherent biases to overcome.

- There is even an Eradicate Hate Summit happening this fall, which will examine strategies on how to overcome the biases that lead to violent acts.

Progress from the 1980s — Present

In June of 1981, the first five cases of a mysterious disease, originating in gay men living in Los Angeles, were cited in an article authored by the Center for Disease Control (CDC). Almost immediately, they began receiving calls from multiple locations around the country, including New York City and San Francisco, of similar cases. Over 300 were reported by December of that same year.

By the fall of 1982, the mysterious condition had a name, Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) and the first deaths had occurred—some of whom were infants, indicating this was not just a sexually transmitted disease, but one that could be passed from parent to child and also spread through blood transfusions or intravenous drug use.

In early 1983, San Francisco opened the first-ever AIDS outpatient clinic, and that spring, the first front-page story about the disease ran in the New York Times.

By the end of 1985, the HIV virus had been identified, and the United Nations reported that at least one AIDS patient had been found in every region of the world. 6,000 people died of AIDS that year.

In early 1987 the first antiretroviral drug, zidovudine (AZT), originally for those suffering from cancer, was approved to treat AIDS patients. In April of that same year, Princess Diana was filmed shaking the hand of an HIV patient in London, thereby removing much of the fear that had been spread to deter people from interacting with those afflicted.

By 1992, AIDS became the leading cause of death for men aged 25 – 44.

In 1994, AIDS became the leading cause of death for both men and women in that same age group.

By 1999, the World Health Organization reported that 14 million people had died from AIDS, which made it the fourth biggest killer worldwide.

Throughout the early 2000s, additional antiretroviral drugs were approved, thereby reducing deaths considerably for those living with HIV.

In 2023, the first HIV vaccine trials began in the U.S. and South Africa.

Current Challenges

The contraction of HIV is no longer a death sentence for several, thankfully, due to increased education and the availability of treatments, but that’s not the case for everyone. Many communities are still gravely impacted by the disease and rely on support from the Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) global health program to survive. The initiative, started by the U.S. President George W. Bush during his first term in office, has saved an estimated 26 million lives.

Last month, Wired reported that sweeping infrastructure changes in the U.S. have prevented USAID funding—which over 130 countries rely upon—from reaching its approved beneficiaries. This specifically impacts AIDS relief, though it was supposed to be exempt from the cuts.

How to Help

Though it may take time for lawmakers in the U.S. to restore the flow of funding to its intended sources, we have several partners and friends doing incredible work in the HIV/AIDS space, who could use your support in the meantime:

amFAR is one of the world’s leading nonprofits dedicated to the support of ending AIDS through research, education and advocacy. Since 1985, they have awarded nearly 4,000 grants to research teams worldwide, and raised a total of nearly $900 million.

Elton John AIDS Foundation supports organisations around the world to increase healthcare, eliminate LGBTQ+ stigmas and advocate for equal rights in the communities that need it the most. Founded in 1992, they have raised more than $600 million to support projects in 95 different countries.

Studio Samuel includes HIV/AIDS prevention education and testing through their Training for Tomorrow program in Ethiopia. The group, currently celebrating their 10th anniversary, focuses on young girls in poverty-stricken areas. Since the HIV/AIDS curriculum began, 100% of the students have tested negative for the disease.

If you’re unable to donate, there are other ways to make a difference, through community advocacy (Americans: call your state senators and representatives), and get involved in events, online campaigns and more.

Everyone is needed to reverse this outcome and continue with the good work that has already made such a difference.

When we stand together, we stand a much better chance of making positive progress a reality….

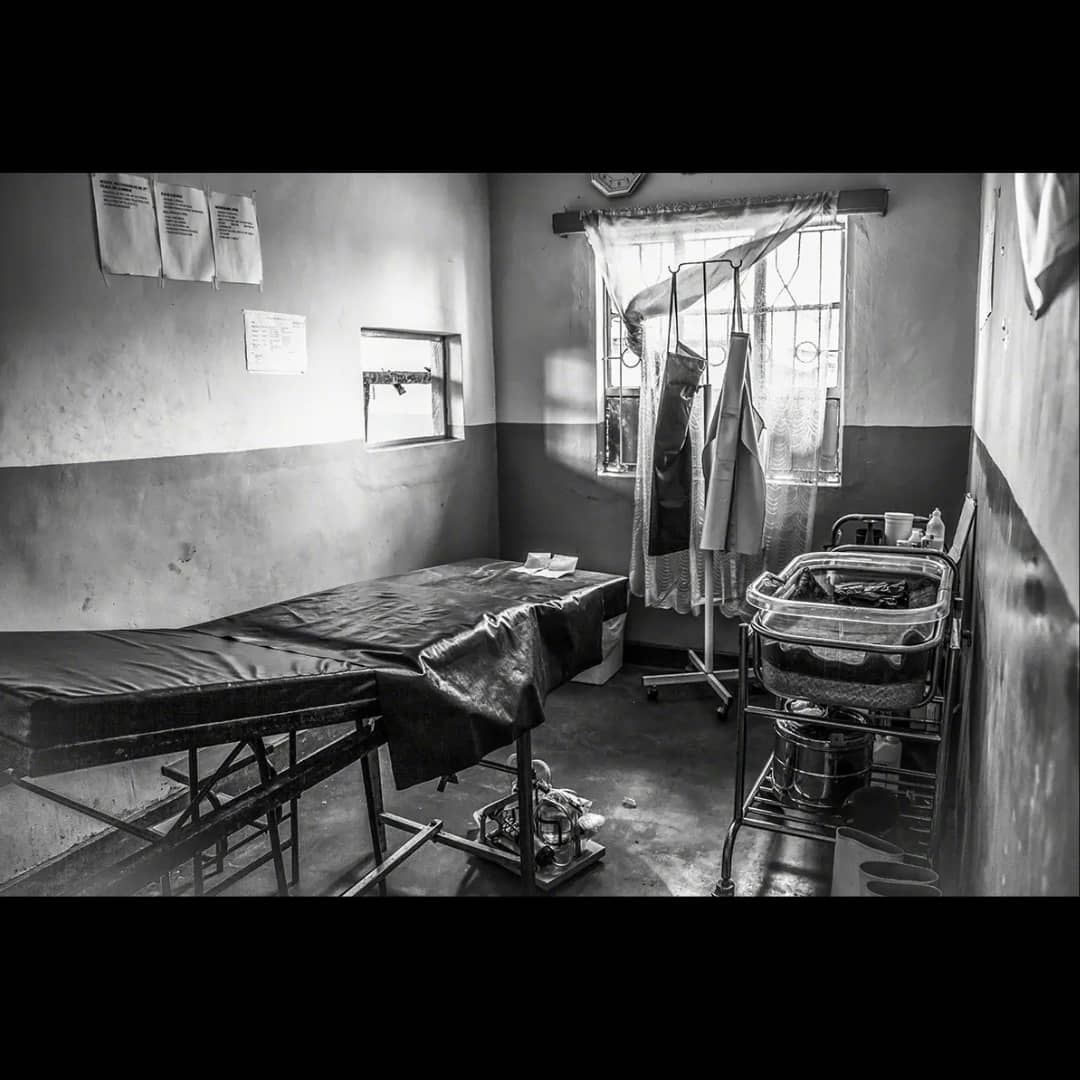

“Prayers” © 2014, by Julian Lennon. View Julian’s full Kisumu-Kenya collection at julianlennonphotography.com.

To become a member of The Pulse, which is our TWFF monthly donor program that supports Education & Health projects, start here.

Great, thanks Star 3/12/2025

I remember when it started. And how people put the blame on the LGBT community. I head a woman daring to suggest all gays should be killed. So good to know things are changing for better. May a vaccine comes soon.

I love it.